Backyards prove surprising havens for native birds

Tucked away from judging eyes, backyards are unexpected treasure troves of resources for urban birds.

ESA Centennial Annual Meeting, August 9-14, 2015 in Baltimore, Md.

ESA Centennial Annual Meeting, August 9-14, 2015 in Baltimore, Md.

Ecological Science at the Frontier

Many of us lavish attention on our front yards, spending precious weekend hours planting, mowing, and manicuring the plants around our homes to look nice for neighbors and strangers passing by. But from the point of view of our feathered friends, our shaggy backyards are far more attractive.

Is a robin eating backyard pokeweed berries a welcome visitor or weed-spreading nuisance? Credit, C. Whelan.

So found ecologist Amy Belaire when she surveyed human and avian residents in 25 Cook County neighborhoods in suburban Chicago. She will present her research during the 100th Annual Meeting of the Ecological Society of America on August 9–14, during a session on Urban Ecosystems that also includes Caroline Dingle’s observations on how birds modulate their songs to be heard over the noise of daily life in Hong Kong, and Kara Belinsky’s exploration of how many trees it takes to make a forest (from a bird’s point of view) in suburban New York.

Belaire, a natural resources manager and education and research coordinator at St. Edward’s University’s Wild Basin Creative Research Center in Austin, Tex., and her colleagues Lynne Westphal (USDA Forest Service) and Emily Minor (University of Illinois Chicago) asked people about their perceptions and awareness of birds in their neighborhoods and how they felt about having birds around their homes. They also asked about the yard design and management choices that residents make in both front and back yards. The researchers also looked at socioeconomic factors and used statistical analysis to tease out the relative importance on yard management choices of neighbors, factors like income, and perceptions of local birds.

“The cool thing about this is how much it reveals about backyards,” said Belaire. “Our most interesting take-away is that backyards tend to be treasure troves of ecological resources. It’s where you find a lot of factors helpful to native birds—more vegetation complexity, more plants bearing fruits and berries—and more design with the intention of attracting birds.”

When planting and cultivating their front yards, people seemed most motivated by what their neighbors were doing. But in managing backyards, perceptions of birds became important to residents. This suggests that local birds may motivate stewardship. People enjoyment of and appreciation for birds appears to translate into on-the-ground effects, at least in backyards.

Examples of front yards in Belaire and colleagues’ study area in the greater Chicago region.

Credit: E. Minor.

Belaire found a surprising 36 bird species living in or passing through the Chicago neighborhoods. In landscapes increasingly sublimated to human industry, parks and yards within cities are potentially essential habitat for local birds as well as oases for birds stopping by on long seasonal migrations. Belaire and colleagues want to know what motivates people in the design of their yards, and what yard elements matter the most to the birds.

Models of her data indicated that the resources in groups of neighboring yards were, as clusters, more important for predicting the diversity and distribution of bird species than measurements of whole neighborhood, or landscape scale, tree cover. In Cook County, backyards with more trees, especially a mix of evergreen and broadleaf trees, more fruit and berries, and fewer outdoor cats had more native bird species. Bird feeders did not have an effect on the number and diversity of birds.

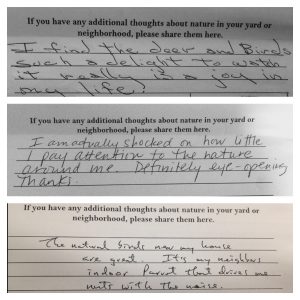

Belaire said she and her colleagues were cheered by the excellent response rate to the survey and the overall enthusiasm of residents.

“I think it was because of the subject matter. Birds are something that people care about and are excited about,” she said. “I was surprised by how much people enjoyed being part of a scientific study and felt honored to be asked.”

The importance of yard-scale land management choices in boosting the presence of native bird species in urban areas was also encouraging for its implications for outreach programs. The efforts of individuals can make a difference and many people care about outcomes for birds. In the future, people may even be influenced by neighbors to make changes that could help birds thrive.

Cook County, Ill. homeowners respond to survey questions about nature in their yards or neighborhoods. Courtesy, J. Amy Belaire.

“It’s empowering,” said Belaire. “Every little bit matters.”

Different social drivers, including perceptions of urban wildlife, explain the ecological resources in front vs. back yards (COS 151-4)

J. Amy Belaire, Wild Basin Creative Research Center, St. Edward’s University, Austin, TX

Friday, August 14, 2015: 9:00 AM, rm 347.

More meeting sessions on urban birds:

- COS 151-2 A coo story: Both oscine and non-oscine birds adjust their songs in noisy cities

Caroline Dingle, Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hong Kong,

Friday, August 14, 2015: 8:20 AM, rm 347 - COS 151-9 Avian diversity and abundance on a suburban university campus: Are trees enough to make a forest from a bird’s point of view?

Kara L. Belinsky, Biology, SUNY New Paltz

Friday, August 14, 2015: 10:50 AM, rm 347 - COS 93-7 Effects of urban noise, irrigation, and neighborhood socioeconomics on bird communities in Fresno, California

Madhusudan Katti, Biology, California State University, Fresno

Wednesday, August 12, 2015: 3:40 PM, rm 348 - PS 57-168 Improving biodiversity in urban gardens: Determinates of garden bird abundances in Greenville County, SC

Katherine B Murray, Biology, Furman University

Wednesday, August 12, 2015, 4:30-6:30 PM, Exhibit Hall - PS 58-198 UrBioNet: A global network for urban biodiversity research and practice

Myla F.J Aronson, Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Natural Resources, Rutgers University

Wednesday, August 12, 2015: 4:30-6:30 PM, Exhibit Hall

The 100th Annual Meeting of Ecological Society of America convenes this August 9–14 at the Baltimore Convention Center in Baltimore, Md. The centennial meeting is on track to be our biggest gathering, with 4,000 presentations scheduled on topics from microorganisms to global scale ecological change.

ESA invites press and institutional public information officers to attend for free. To apply, please contact ESA Communications Officer Liza Lester directly at llester@esa.org. Walk-in registration will be available during the meeting.

The Ecological Society of America (ESA), founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 10,000 member Society publishes six journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://esa.org.