Sneaky mating may be in female damselfies’ interest

New research on damselflies in northern Africa suggests that females may facilitate the reproductive success of inferior males when their health is at risk

July 8, 2019

For Immediate Release

Contact: Zoe Gentes, 202-833-8773 ext. 211, gro.asenull@setnegz

A Glittering Demoiselle (Calopteryx exul) dragonfly perches on a leaf. Photo courtesy of Mroede/Wikicommons.

During the mating season, male damselflies battle fiercely for control of prime territories containing resources – typically patches of floating leaves used for egg deposition in wetlands – that are key to attracting females. To the victors go the spoils: though a dominant male must then diligently guard his hard-won territory against interlopers, ownership of a territory gives him exclusive access to the females that congregate within his domain.

Some of his rivals, however, refuse to play by the rules.

Instead of expending energy squabbling over territorial rights, rival males simply perch on nearby vegetation and await opportunities to swoop in and steal females from a dominant males’ territory. Although the reproductive benefits of engaging in this kind of “sneaky mating” behavior are readily apparent for the sneaker males, females in contrast would seem to have little to gain from mating with inferior, non-territorial males. Moreover, there should be strong evolutionary selection pressure against sneaker male phenotypes. How and why sneaky mating behaviors arise and persevere therefore remains something of a mystery.

A new analysis of the mating behavior of a rare African damselfly that is endangered according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, published in the Ecological Society of America’s journal Ecology, suggests, however, that sneaky male phenotypes may endure in a population because females do in fact derive reproductive benefits from sneaky mating under certain conditions.

In this study, Rassim Khelifa, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of British Columbia’s Biodiversity Research Centre, conducts surveys of egg-laying females in an unusually large population of Calopteryx exul (Glittering Demoiselle) – a damselfly found only in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia – in 2010 and 2011. His results indicate that the frequency of sneak attempts in this species is density-dependent, and thus sneaker male success rates track with changes in population abundance. “Sneaking attempts are more likely to be observed when the population is large,” explains Khelifa. “That is, high population density promotes sneaky behavior, and is mainly driven by the limited availability of oviposition [i.e. egg-laying] patches that attract females.”

Male C. exul have genital structures that enable them to remove sperm from the female reproductive tract, and egg fertilization results from the final mating, an adaptation known as “last sperm precedence.” The continued existence of sneaky mating behavior in these damselflies is thus dependent not only on the ability of sneaker males to mate with harem females, but also on post-mating female behavior, as sneaker male paternity will only be ensured if the female does not subsequently copulate with any other male.

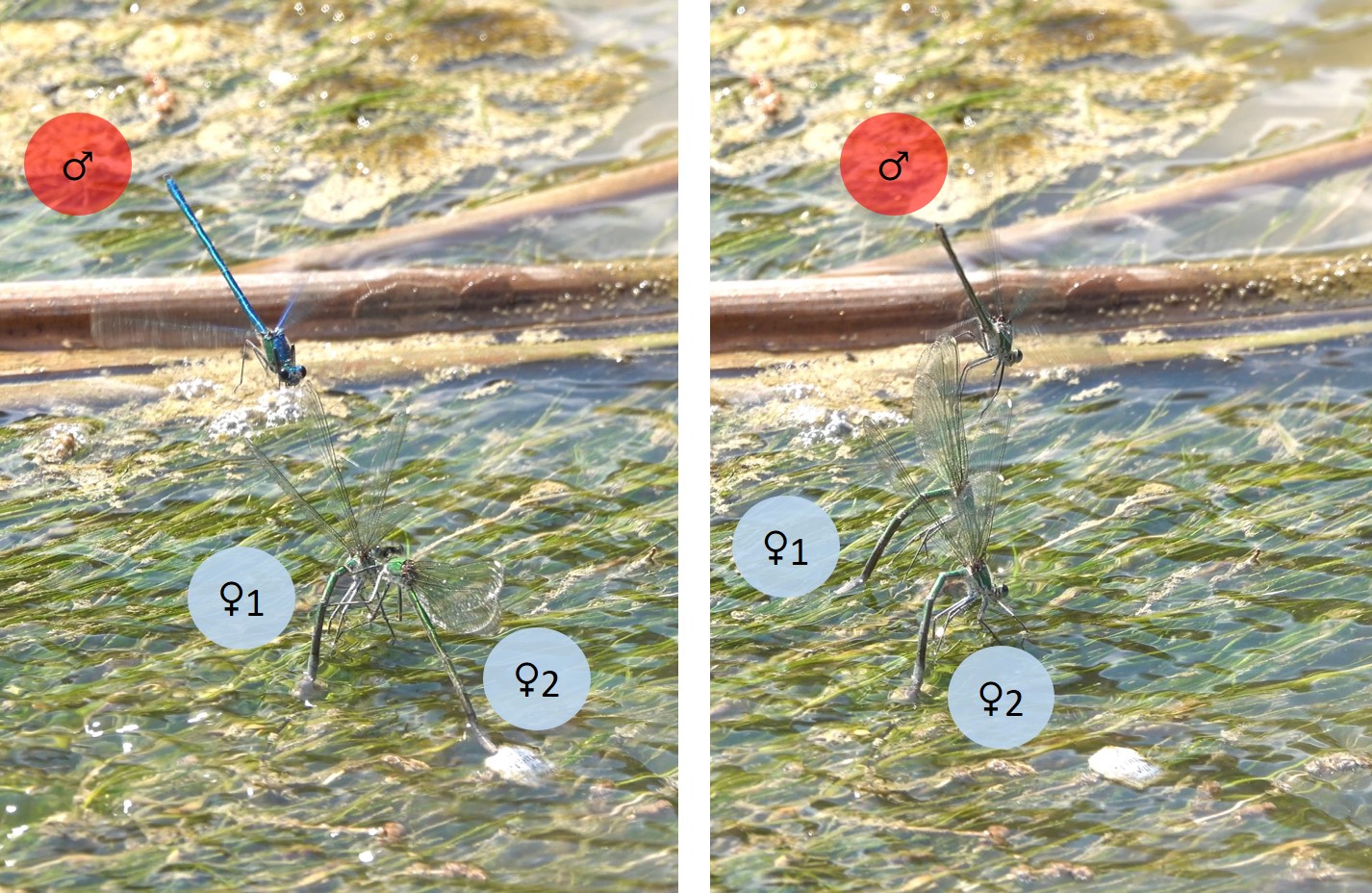

On the left, Female 2 lands very close to Female 1 to avoid harassment by the dominant male. On the right, the male misrecognizes the Female 2 and harasses Female 1. Thus, Female 2 (carrying sneaker male sperm) avoids risking bodily harm by avoiding further mating in a heavily populated territory. Photo courtesy of Rassim Khelifa.

But why would a female damselfly purposefully avoid mating with a dominant male after mating with a sneaker male? Mating in species with territorial mating systems involving last sperm precedence is often aggressive, and multiple copulations may cause serious injury to females, says Khelifa. “If a female was forced to copulate with a sneaky male, and that extra-copulation damages her reproductive tract, then she will tend to avoid recopulating with the territorial male,” he explains. She avoids the extra mating to preserve her health. Because females can evade the attentions of a dominant male more easily when there are many other females in his territory, a sneaker male stands a better chance of being a females’ last partner when population abundance is high.

Such complex sexual interactions and conflicts over access to dominant males, females, and egg-laying sites can lead to alternative mating strategies in which females appear to reduce their own reproductive fitness costs by contributing to the reproductive success of non-dominant males, even if indirectly. “Understanding the mechanisms responsible for the existence and maintenance of phenotypic variability in natural populations is a central question in evolutionary biology,” according to Khelifa. “The results of this analysis suggest that the fitness of sneaker males might not be as low as we think, and that the success of sneaky strategies depends greatly on female behavior following copulation.”

Once widespread throughout its three-country range, the Glittering Demoiselle now only lives in segmented, isolated populations. Its wetland habitat is disappearing due primarily to habitat loss, pollution, drought and streams that are drying up due to a changing climate. “Amazing natural history stories that might advance our evolutionary thinking are still hidden in species that have received little research attention,” says Khelifa, but he warns that many such tales are being lost as populations – and entire species – dwindle and disappear worldwide. Indeed, the population of damselflies that was the focus of this study – and the largest congregation of C. exul ever recorded within its geographical range – has since vanished.

Journal article

Authors

Rassim Khelifa; Biodiversity Research Center, University of British Columbia

Author contact:

Rassim Khelifa moc.liamgnull@afilehkmissar

###

The Ecological Society of America (ESA), founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 9,000 member Society publishes five journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 3,000-4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://www.esa.org.