Shrinking shark numbers on Great Barrier Reef unlikely to have cascading impacts

New evidence suggests that reef sharks exert weak control over coral reef food webs; environmental features play a more definitive role

February 18, 2021

For Immediate Release

Contact: Heidi Swanson, (202) 833-8773 ext. 211, gro.asenull@idieh

Shark populations are dwindling worldwide, and scientists are concerned that the decline could trigger a cascade of impacts that hurt coral reefs. But a new paper published in Ecology suggests that the effects of shark losses are unlikely to reverberate throughout the marine food web.

Instead, the findings point to grassroots-level features, like the structure of coral reefs and patterns of water movement, as important regulators of coral reef communities.

Lead author Amelia Desbiens, a marine ecologist at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, conducted the study using data collected by the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation during its 2014 Global Reef Expedition, which surveyed shark populations on the northern Great Barrier Reef.

The Living Oceans Foundation can access remote reefs throughout the world on their research vessel, the Golden Shadow. Photo courtesy of Bar Ayalon/Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation.

Back then, this area was one of the most pristine reef regions in the world. The divers were heartened by the dizzying array of fish species in some locations, counting a total of 433 species of coral reef fish across their study area. They also found that no-fishing zones had four times as many reef sharks as the zones that allow fishing.

“With shark populations around the world being threatened by overfishing, it was great to see high numbers of reef sharks in protected areas across the northern Great Barrier Reef,” said Desbiens. She and her colleagues wondered whether an abundance of reef sharks might mean healthier corals – and, conversely, whether over-fishing could have a trickle-down effect that hurts corals.

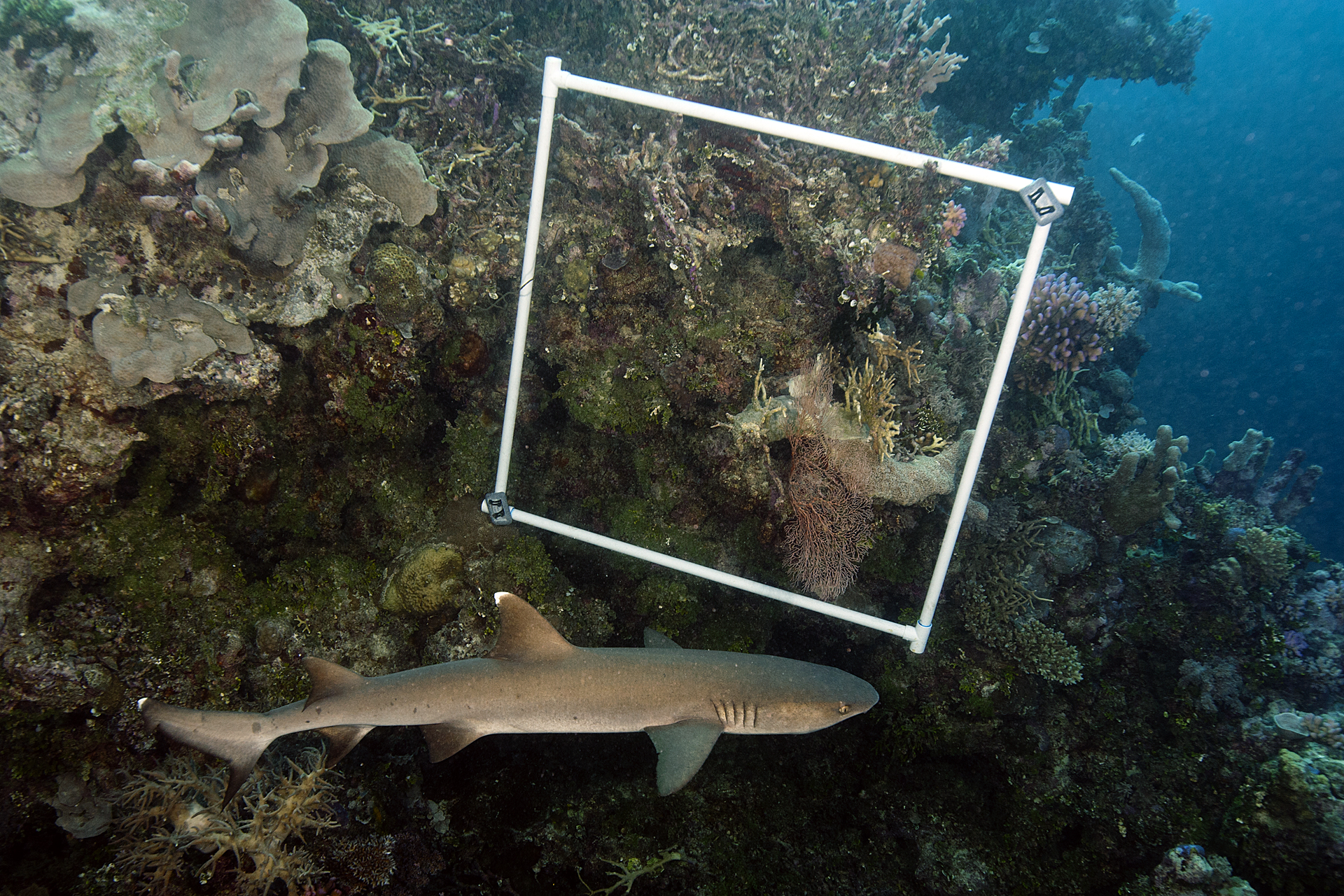

A whitetip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus) swims near a square frame used to survey corals. Photo courtesy of Ken Marks/Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation.

There is plenty of precedent for the idea: in many ecosystems, the disappearance of top predators can create a domino effect for the rest of the food web, perhaps most famously seen with the decline and eventual re-introduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park. On the Great Barrier Reef, Desbiens and her team expected to see sharks keeping smaller predatory fish in check, which would allow even smaller seaweed-eating species like parrotfish to thrive. Seaweed can choke out corals, so a strong presence of seaweed-eating fish helps maintain healthy reefs.

However, contrary to their expectations, the team found that reef shark density only had a small influence on the abundance of prey species.

Control of the system seemed to point in the other direction. Physical features of the environment, such as higher levels of coral reef complexity and lower levels of wave exposure, were associated with higher shark abundance.

In some ways, the findings are encouraging, because they suggest that a reef shark downturn is unlikely to result in a seaweed explosion that could hurt corals. But the colorful reefs face threats beyond overfishing.

Large mounds of Porites lobata and round thickets of Porites cylindrica in the shallows. Photo courtesy of Ken Marks/Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation.

“We were fortunate enough to survey the far northern Great Barrier Reef in 2014, when these reefs were considered remote and fairly untouched,” said Desbiens. “Unfortunately, in the years after our survey, these reefs were decimated by back-to-back coral bleaching events, which caused mass mortality of many corals in the region.”

Still, the loss offers new learning opportunities. Because the study found a strong link between living coral cover and shark numbers, Desbiens and her colleagues now hope to revisit the same study sites to see how sharks have responded to the loss of corals in the region.

Journal article:

Desbiens, Amelia A., Roff, George, et al. 2021. Revisiting the paradigm of shark‐driven trophic cascades in coral reef ecosystems. doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3303

Authors:

Amelia A. Desbiens1, George Roff1, William D. Robbins2,3,4,5, Brett M. Taylor6, Carolina Castro-Sanguino1, Alexandra Dempsey7 and Peter J. Mumby1

1Marine Spatial Ecology Lab, School of Biological Sciences & Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia; 2Wildlife Marine, Perth, Western Australia, Australia; 3Department of Environment and Agriculture, Curtin University, Perth, Western Australia, Australia; 4School of Life Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; 5Marine Science Program, Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, Perth, Western Australia, Australia; 6The Australian Institute of Marine Science, Crawley, Western Australia, Australia; 7Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Annapolis, United States of America

Author contacts:

Amelia Desbiens (ua.ten.qunull@sneibsed.a)

George Roff (ua.ude.qunull@ffor.g)

Peter Mumby (ua.ude.qunull@ybmum.j.p)

###

The Ecological Society of America, founded in 1915, is the world’s largest community of professional ecologists and a trusted source of ecological knowledge, committed to advancing the understanding of life on Earth. The 9,000 member Society publishes five journals and a membership bulletin and broadly shares ecological information through policy, media outreach, and education initiatives. The Society’s Annual Meeting attracts 4,000 attendees and features the most recent advances in ecological science. Visit the ESA website at https://www.esa.org.