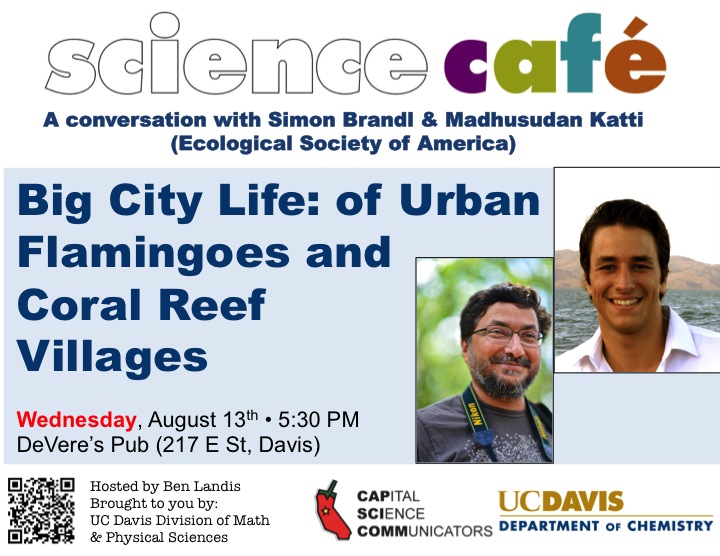

When: Wednesday, August 13, 5:30 pm.

Where: DeVere’s Irish Pub, 217 E St, Davis, Cal.

Getting there from the Sacramento Convention Center:

If you don’t have wheels, the best transport option is Amtrak’s Capitol Corridor trains, which leave from the Amtrak station 0.7 mile from the Convention Center (see walking maps below).

Westbound to Davis (going), take the #545 train departing Sacramento at 4:40 pm; arriving in Davis at 4:55 pm.

Eastbound to Sacramento (return), trains leave Davis at 7:07, 8:27, and 9:52 pm.

Full schedule [pdf].

Be sure to leave plenty of time to hike from the ticketing counter to the platform in the Sacramento Amtrak station.

Walking directions: Sacramento Convention Center to Amtrak Station (0.7 mi).

Be sure to leave plenty of time to hike from the ticketing counter to the platform in the Sacramento Amtrak station.

Walking directions: Davis Amtrak Station to Devere’s Pub (0.2 mi)

Winning 2014 Science Cafe Contest Pitches from Katti and Brandl:

Madhusudan Katti

Mention wildlife to a city dweller and images of remote nature will probably come to mind – not an empty lot around the corner. Wildlife, after all, should occur in wild places. But cities can support many species and this has implications for conservation efforts.On a crowded planet, protecting species in their natural habitat is proving increasingly difficult. By 2030, cities are expected to occupy three times as much land as they did in 2010. Remaining natural habitats are often fragments caught in this global web of cities connected by transportation networks. With the number of species going extinct on the rise, we must consider the potential of urban environments to support wildlife.

I am part of a new global network of urban ecologists and naturalists—UrBioNet—compiling biodiversity data to assess how many species manage to survive in cities worldwide. Our recent analysis of plant and bird diversity found that cities have lost an average of one-third of the species native to their region. While this is worrying, it is worth noting that two-thirds of the native species continue to occur in cities that were never designed to support wildlife. In fact at least 20% of the world’s known bird species now occur in urban areas, as do at least 5% of the known plant species.

With more conscious green landscape designs, imagine how many more of the native wildlife we might accommodate in our cities? Wildlife conservation can indeed start at home on our urban planet.

Simon Brandl

Munich, my hometown, capital of Bavaria, Germany:Besides short periods of time during which the world closes in to drink beer, Munich is a quiet and picturesque community with numerous historic sites and businesses, featuring, for instance, old bakeries, butcher shops, and, of course, breweries. Most of the latter appear to occupy a distinct niche, having specialized on a restricted range of products.

Great Barrier Reef, Australia:

Besides short periods of time during which the world closes in to find Nemo, the Great Barrier Reef is a quiet and picturesque city, consisting mostly of historic sites and inhabitants, featuring, for instance corals, algae, and, of course, fish. Most of the latter appear to occupy a distinct niche, having specialized on a restricted range of resources.

De Vere’s Pub, Davis, California, USA:

Not solely intended as an exercise in sneaking ecological jargon into a non-ecological context, the previous paragraphs show that man-made environments can exhibit striking similarities to natural systems. Here, I will risk a geographically humungous split between Munich and the Great Barrier Reef to highlight recent advances in our understanding of coral reefs – in other words, I will introduce butchers, bakers and brewers in one of the world’s most spectacular and diverse ecosystems and, in their company, illustrate why modern coral reefs look the way they do and why brewers are particularly important. The intentional replacement of the traditionally cited candlestick maker may hereby be due to Bavarian heritage or the proposed venue.